Turkey's Earthquake, One Year On: Press Freedom Under Siege During and After the Disaster

How the government's response to the disaster sparked a press freedom crisis, with fines, detentions, and social media attacks targeting reporters

On February 9, 2023, a devastating earthquake shook Turkey to its core, leaving behind a trail of destruction and despair. As the nation grappled with the aftermath of this natural disaster, journalists embarked on a mission of utmost importance — to report the ground reality and coordinate aid efforts. However, their efforts were met with numerous obstacles and press freedom violations.

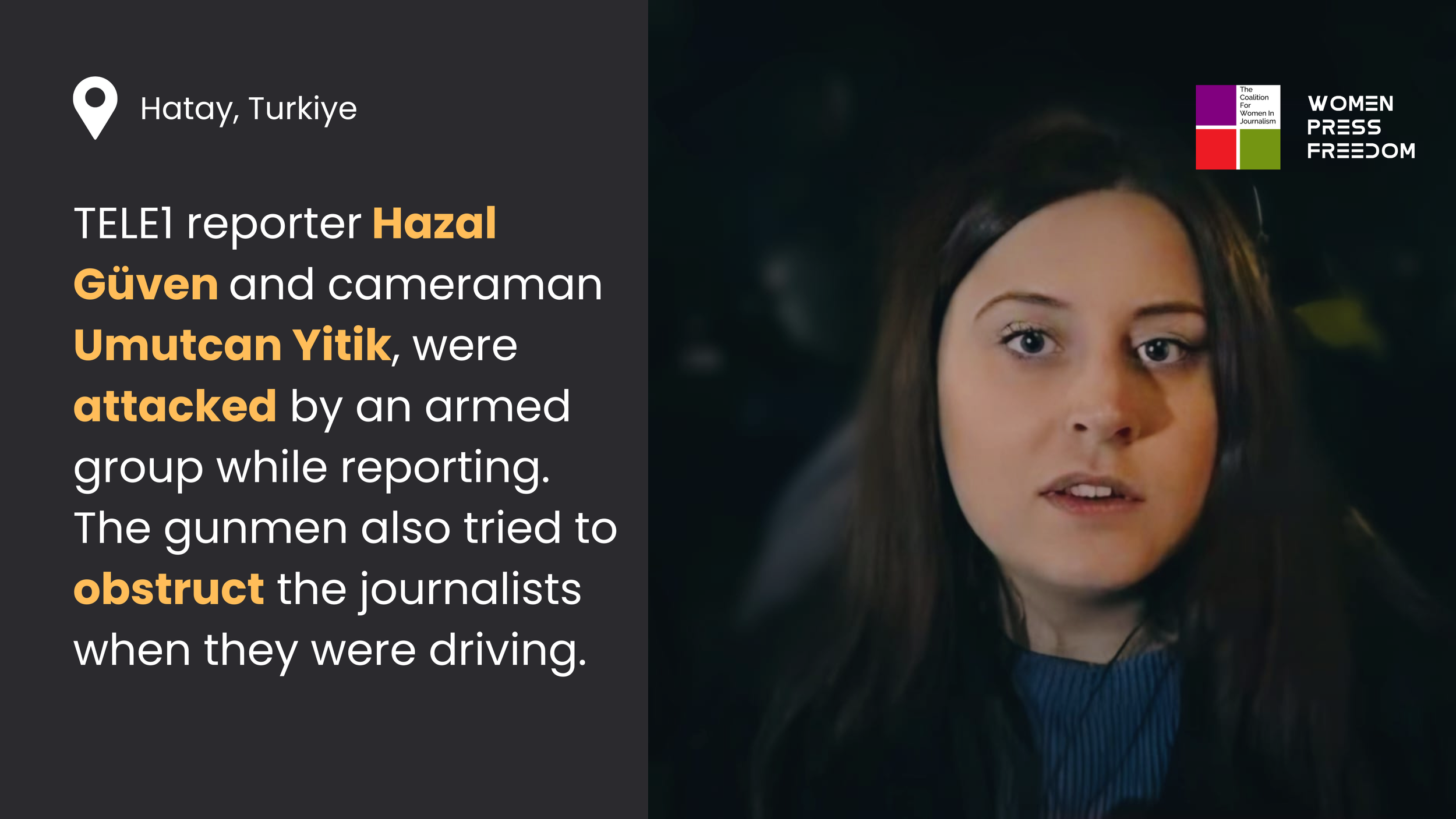

“They cut us off. They pulled out a gun,” shared TELE1 reporter Hazal Güven on Twitter after being attacked by an armed group while on assignment in Hatay, following government officials' targeting of journalists. “Our hands are still shaking. The security problem in the region has reached a very serious level. "

“They cut us off. They pulled out a gun”

One of the most significant alerts was the 12-hour blocking of Twitter, which prevented the circulation of news and hindered search and rescue efforts on the third day after the earthquakes.

As if the challenges weren't already substantial, the broadcasting regulatory authority, RTÜK, began imposing fines on media outlets for their critical reporting of the government's response to the disaster and for raising questions about the role of illegal constructions in contributing to the extent of the devastation.

Prior to this, police in the affected areas started demanding "turquoise press cards," causing delays for those journalists who had disagreements with authorized institutions in the past. In some harrowing instances, journalists were detained and interrogated for not possessing these specific press credentials, despite holding valid press cards issued by media organizations.

“They took my camera from me and said it was forbidden for me to be in the area,” Gülbahar Altaş told Women Press Freedom on February 9th after police obstructed her while filming in Diyarbakır on February. “First, they deleted the photos I took at the debris site. Then, they took a photo of my press card. When I said, 'What do you think you're doing? You don't have the right to delete my photos,' they took the memory card from my camera.”

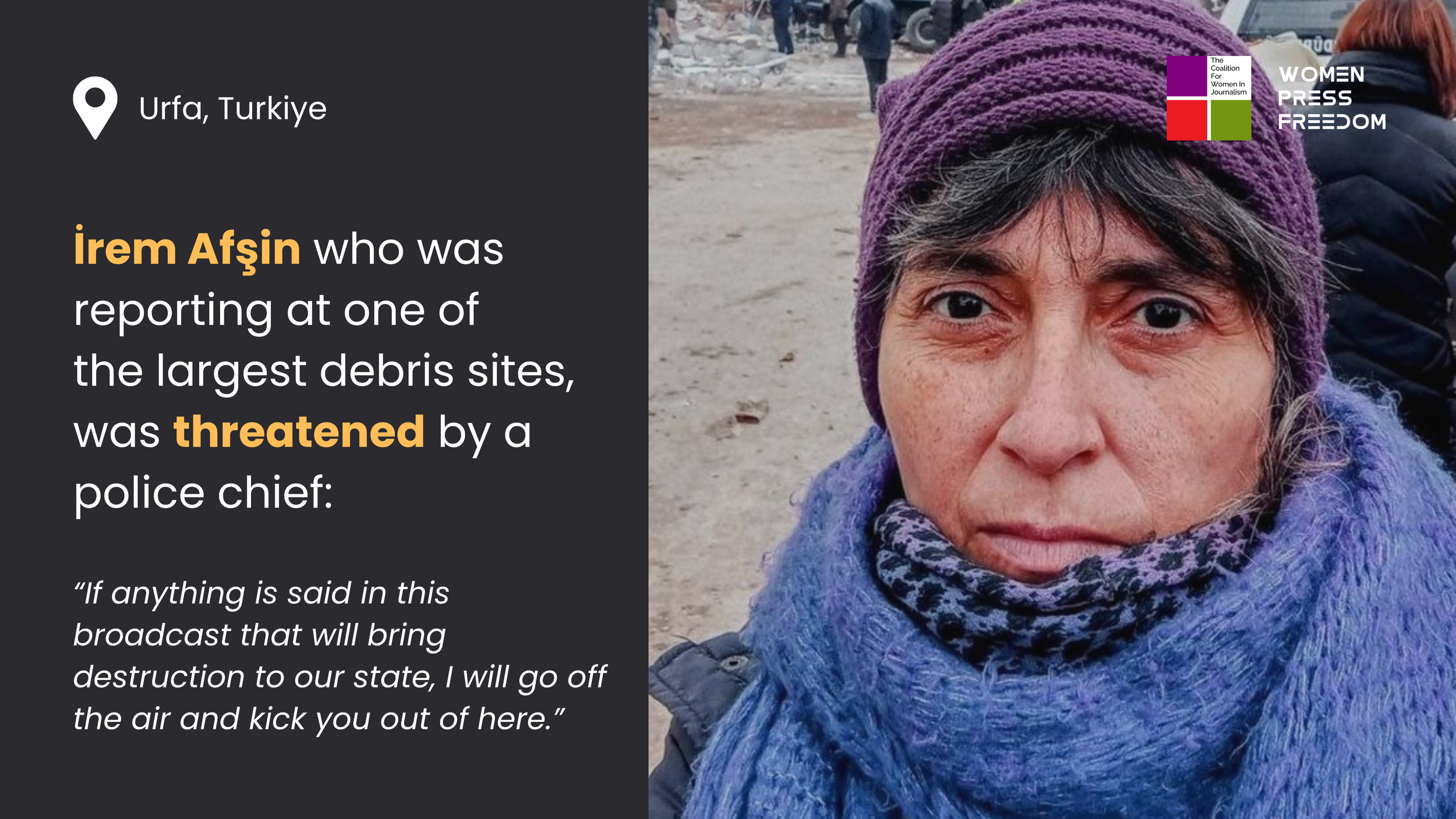

In Urfa, journalist Sema Çağlak and her colleagues were detained for reporting on earthquake victims and wreckage. They were held for questioning, and their press cards were confiscated, further obstructing their ability to do their job. In Diyarbakır, a police chief tried to prevent journalists from filming a collapsed residence, forcing them to obtain additional accreditation cards, further complicating their work. These hostile reactions from both authorities and the public created an atmosphere of fear and danger for journalists.

“They (police) took my camera from me and said it was forbidden for me to be in the area”

Press freedom violations transcended the physical realm, extending into the digital domain. Some pro-government journalists accused their colleagues of propagating for terrorist organizations and inciting hatred against the state on social media, further escalating tensions and endangering journalists' lives.

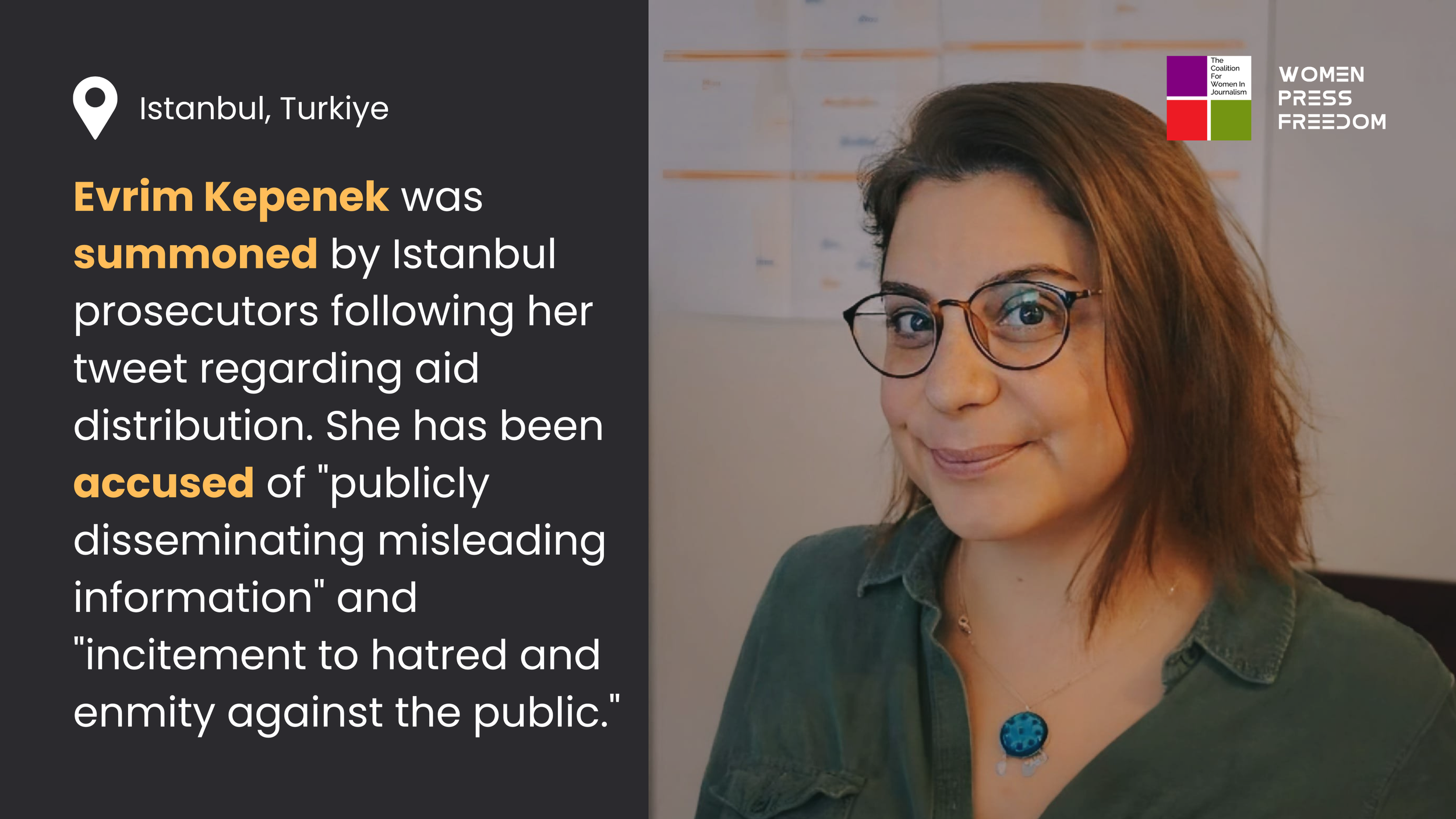

Even after the initial crisis, journalists continued to face legal action for their reporting. Journalist Evrim Kepenek, for example, is under investigation for tweets regarding aid distribution following the earthquake. She faced allegations of "publicly disseminating misleading information" and "incitement to hatred and enmity against the public." These charges, framed under the "disinformation law," carry the threat of imprisonment.

As we solemnly mark the one-year anniversary of the devastating earthquake in Turkey, it is imperative to emphasize the critical role of press freedom during natural disasters and their aftermath. The press serves as a lifeline for many, providing information, coordinating aid, and holding authorities accountable.

The violations of press freedom witnessed during this crisis underscore the dangers of an information vacuum and the importance of ensuring journalists can do their jobs without fear of harassment or censorship. The press should be supported and protected, not hindered, during such calamitous events. Journalism is not a crime; it is a lifeline for those in need.

The Coalition For Women In Journalism is a global organization of support for women journalists. The CFWIJ pioneered mentorship for mid-career women journalists across several countries around the world and is the first organization to focus on the status of free press for women journalists. We thoroughly document cases of any form of abuse against women in any part of the globe. Our system of individuals and organizations brings together the experience and mentorship necessary to help female career journalists navigate the industry. Our goal is to help develop a strong mechanism where women journalists can work safely and thrive.

If you have been harassed or abused in any way, and please report the incident by using the following form.